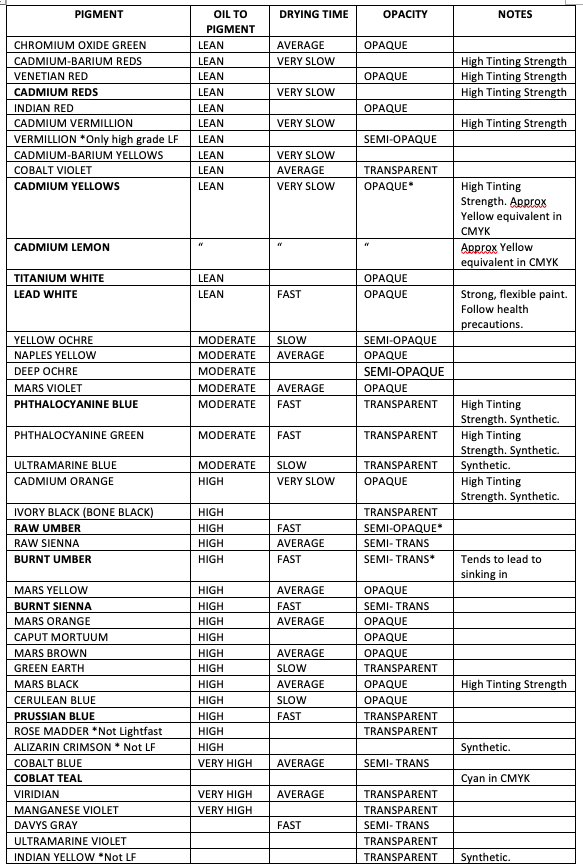

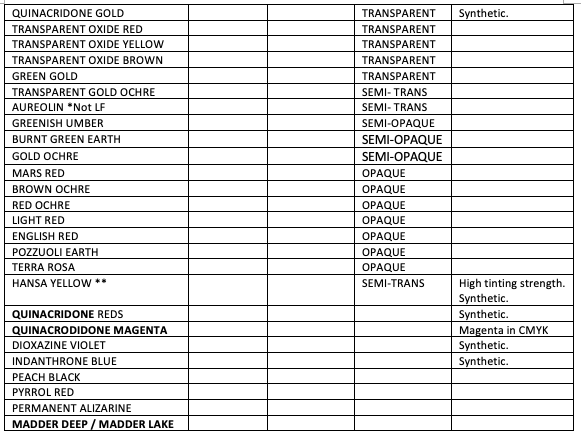

A guide to Pigment drying times in oil painting

Recently I donated some mediums I haven’t used in years to a local artist. The mediums were in a ‘3 step’ formula where Medium 1 was designed to provide a lean underpainting, Medium 2 a slightly fatter layer, and Medium 3 to provide the slowest drying layer of them all for the final touches. I offered the mediums for free on my socials and explained that I only used them once on a painting titled ‘Boats by Birkenhead’ and after it’s completion I buried myself in research to learn about the properties of the pigments themselves. I rely on this knowledge now to create paintings that adhere to the fat over lean principal.

Painting fat over lean is important in oil painting as it means that the upper layers do not cure before the under layers are dry which can lead to cracking.

The benefits of being selective and sparing when adding medium relates to creating a strong infrastructure in the painting and to avoid yellowing. After centuries of artists grinding different materials to see if they could be blended with a drying oil and turned into a usable paint, we are lucky to be the benefactors of their experiments (and failures) and know what pigments stand the test of time. We are so spoiled that we do not even have to mull our paints ourselves and can buy paint ready made and labelled with how lightfast they are on the tube. The strongest and most lightfast element of our paints are the grains of pigment. These grains of pigment look like boulders under a microscope and are suspended in a drying oil (most commonly linseed is oil). A drying oil is necessary to turn the ground pigment dust into something we can paint with, however this oil and any other medium added is the element susceptible to yellow and become brittle. When medium is added sparingly we effectively get a painting built with lots of those pigment ‘boulders’ close and “locked” together creating a strong structure.

There are some effects a painter may like that can only be achieved by either diluting or adding body to the paint with a significant amount of medium, and the pursuit of achieving those effects may outweigh concerns of the potential for cracking, de-lamination and discolouration that can occur to the original art later. Therefore, I would argue that there is no right or wrong way to go about painting, however anyone working with any material will benefit from some understanding of how those materials perform so they can make informed decisions that align with their own intentions and values and the expectations of their target audience to avoid future disappointment.

The below list is an approximation as different paint manufacturers may add various stabilisers and fillers that may affect drying time. The only brand I can think of that doesn’t add stabilisers or fillers is Rublev by Natural pigments.

Though available pigments far extend this collection, this list details the most popular pigments available to contemporary artists and the pigments used in the oil paintings of masters that have stood the test of time.

*Not LF = Not lightfast

**High tinting strength = A little bit of paint will dramatically affect the colour of your mix.

Unfortunately, I haven’t got around to adding the Pigment identifying labels from the Pigment Database so please take the above as a rough guide. For example, Alizarin Crimson is not lightfast as it is pigment PR83, HOWEVER some manufactures will sell a colour called ‘Alizarin Crimson’ but use PR177 or other pigments in the tube.

I stick to a small palette and currently have gaps in the above table on the pigments I do not use and haven’t researched, but might play with in the future.

OTHER PIGMENTS:

LEAD TIN YELLOW + BARITE WHITE (among others) haven’t been included in the above list. Barite White (PW22) is a slow drying transparent white with a low tinting strength. I’ve recently started using it in the upper layers of paintings for glazing and soft highlights. Lead Tin Yellow dries fast.

DRYING TIMES:

All MARS colours have an average drying time.

Most Earth reds have an average drying time.

Ultramarine colours have a slow drying time.

Cadmiums have a very slow drying time.

OPACITY:

Some Burnt umbers are semi transparent, some semi-opaque

Some Raw Umbers are semi Opaque

Some Cadmium Yellows are opaque.

TINTING STRENGTH:

Phthalocyanines have one of the strongest tinting strengths.

Also high in tinting strength: Venetian red, Mars Black, Cadmium colours.

Synthetics usually have high tinting strength.

Pigments high in tinting strength are useful in under paintings when added in small quantities with Lead white. This is because little colour is needed to tint the colour of the paint the introduced oil content from the added oil paint is very low and therefore you have a very lean layer.

PIGMENT ADDITIONAL NOTES:

Burnt Umber: This pigment an inexpensive pigment, useful colour and will speed up drying time, however it is highly absorbent and can cause varnish to sink in. Raw Umber is less problematic and can be a good substitute.

Indian Yellow: Synthetic colour but not all on the market are lightfast. Indian Yellow made with Diarylide yellows, Isoindoline yellows, nickel dioxine yellows and / or synthetic iron oxides are lightfast.

Terre Verte / Green Earth (PG23): Popular pigment in art history. Mined quite extensively and the best pigment is gone.

Cynthia Howard is a contemporary oil painter mixing surrealism and cubism to communicate ideas about our inner world, and our quality of self expression to our outer world.

Artist pictured with ‘A full mind’, Oil on canvas.